“Our very lives depend on the ethics of strangers, and most of us are always strangers to other people.

”

We believe that all international rotations should be conducted in a safe and ethical manner that does not place patients at risk, trainees in situations for which they are not trained, or host sites at a disadvantage for having the trainees present. We expect all our volunteers to follow these principles of an ethical international rotation.

Do no harm

“Almost everyone wants to help. That’s a good place to start, but it’s not enough. The history of development work is a veritable graveyard of good intentions.

”

Whether you are a medical trainee or a seasoned physician, sometimes doing nothing is better than doing something poorly, unsafely, or without supervision. International rotation sites are never places for doing what you would never be allowed to do—or are not comfortable doing—at home.

During your rotation, hold yourself to the same limitations you have at your home institution. If you wouldn’t do something there—a procedure because you’re not yet qualified, a treatment plan because you’ve never seen the disease, a patient counselling sessions because you don’t know the topic—don’t do it at your site.

Know your own limits and be firm about them with people with whom you’ll work. You may feel pressure to act outside of your training—do not do it.

Seek out your own appropriate supervision. If you find yourself unsupervised in a situation with which you are not comfortable, stop.

Even if you are still in training and feel like you “can’t do much,” remember that sharing what you DO already know with your colleagues can be a productive and sustainable activity. Education is something we can always share.

SHOW Respect for youR hosts and colleagues

“...be self-aware about your role and what you will be receiving from the experience.”

Avoid the trap of thinking “I know better than they do” simply because you trained in a western setting. You don’t.

Avoid the “Why don’t they just...” mentality. Systems, structures, politics, and relationships are far deeper and more complicated than you will ever understand during your rotation, and there are usually no quick fixes to problems you see.

Remember that different isn’t necessarily wrong.

When interacting with your colleagues, don’t mistake pragmatism or an ability to choose one’s battles for apathy. Check yourself when (and you will!) catch yourself thinking, “Why does nobody seem to care about this problem?”

Focus on what there is instead of what there is not at your clinical sites; appreciate the creativity and resourcefulness of your hosts. However, don't forget what is lacking, and do brainstorm solutions with your team.

Pay attention to the costs of your presence: gas to drive you somewhere, food provided for your meals, time to teach you, and consumable supplies like gloves and soap that you use. Recognize that your presence has a cost—money, supplies, time—and be conscious to reasonably minimize or eliminate these costs to your host site.

You will have culture shock and it will affect how you view and interact with your environment, colleagues, and people back home. Pay special attention to what you write in public forums during your rotation. Anyone can see your blogs—including people you are writing about.

Show respect TO your patients

“Individuals, regardless of their educational, economic, or cultural background will most always act in the way that they believe to be most beneficial to themselves and their loved ones. More often than not, when it does not seem that someone is acting in this manner, it is because either you or they do not understand the situation. More often than you might expect, it’s you.”

We may not understand the motivations behind our patients' actions, but as visitors, we don’t have to. Assume that people are doing the best that they can, and you’ll be much less frustrated with the cultural differences you’ll see.

Take the time to speak to your patients, even if an interpreter is necessary. Paternalism can exist within any healthcare team. As you’ve most likely come from a culture of patient communication and bed-side rounds, you can be an excellent advocate for your patients.

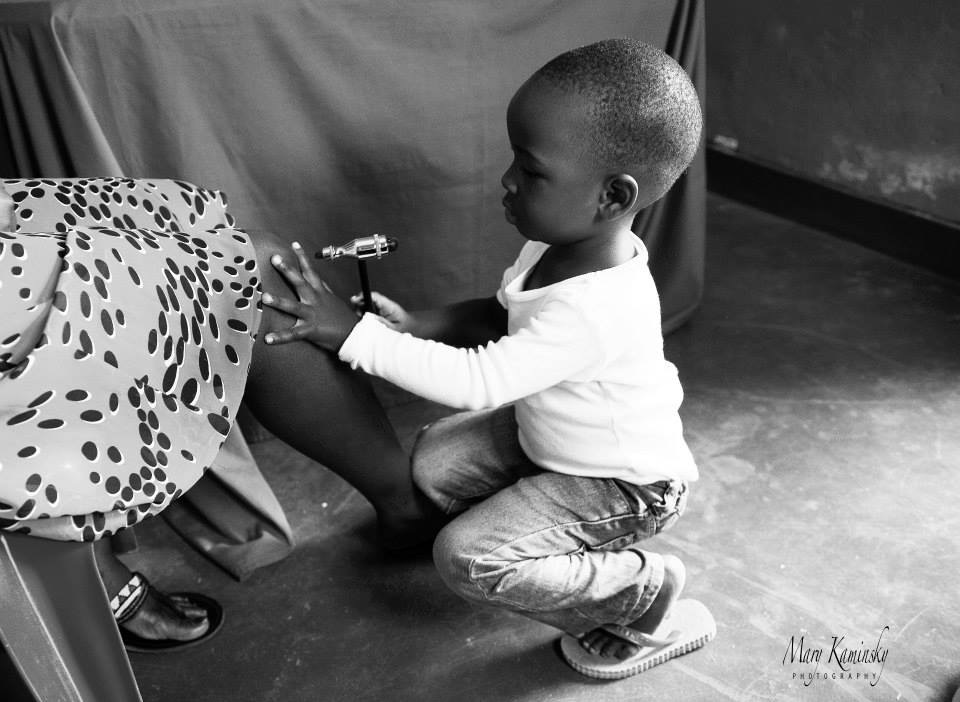

For all photos and videos, do exactly as you would at your home institution: use an “informed consent” approach to explain why you want a picture, who will see it, and what its purpose will be. Tell the patient or parent that they can say no to your request.

Avoid posting any medical photos in public forums. Would you want photos of your sick loved one on someone’s facebook page?

Think about what will happen when you go

Have a counterpart in everything that you do—find an educational buddy! Nothing you do or learn should take away from the educational experience of someone who will be staying longterm at your site. After all, you’re eventually going home—who will be there after that?

Nothing you do or create should leave with you. Nothing should start and end with you alone, so get your colleagues involved.

Always have in mind what will happen to your ideas and projects after you go. Is what you’re doing or saying wanted, helpful, sustainable, or possible when you’re not present? If not, rethink your plans.

Leave your site better than when you arrived, but do it with the support of your national colleagues. Always have an eye toward sustainability of projects and programs and quality improvement.

Recognize your part in the legacy of volunteerism

“As a foreigner from a developed country, almost regardless of your personal history, you are heir to a legacy of explorers, traders, missionaries, colonists, sinners, saints, tourists, and the occasional well-meaning do-gooder....This history has left a legacy that will affect you, both as you walk the streets of your new home and within the project with which you work.”

In the minds of many people you'll meet, you are the same as the person who came before you and the person who will come after you; recognize your role in this continuum and how your actions will affect those who follow you.

Do not give gifts or make promises on behalf of your rotation sites, home organizations, or home hospitals.

Don’t make promises you cannot keep.

Avoid giving trinkets or candy to people. If you plan to bring small gifts, consider pairing them to an educational event for a community or giving them to your host site to decide how best to distribute them.

You will experience racism, and when you do, take the high road.

Remember you represent the larger volunteer community—including everyone who will come after you.

Can we help you find something?